Mamdani: Teenage Activists of ‘Save Darfur’ – Child Soldiers of the West

Once again, Mahmood Mamdani provoked a fervid debate among scholars, activists and other people concerned with politics in Africa. After his controversially discussed comments about Zimbabwe, Mamdani (in his book Saviors and Survivors) accuses the ‘Save Darfur’ campaign in the US to act as the ‘humanitarian face’ of the War on Terror. Read the comments of the Professor at the Columbia University in New York in response to my questions.

Your latest book (besides dealing with the political history of Sudan) is an ardent attack on the ‘Save Darfur’-movement in the US. You call it the ‘humanitarian face of the War on Terror’, their high school activists being the ‘child soldiers’ of the West. Why is it attractive for millions of people in the US to engage in the Darfur campaign?

Your latest book (besides dealing with the political history of Sudan) is an ardent attack on the ‘Save Darfur’-movement in the US. You call it the ‘humanitarian face of the War on Terror’, their high school activists being the ‘child soldiers’ of the West. Why is it attractive for millions of people in the US to engage in the Darfur campaign?

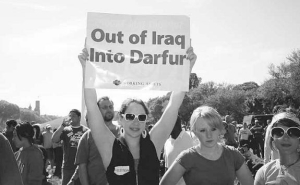

I have pointed out that Save Darfur is not a peace movement but a mobilization for war, something clear from their slogans: ‘Out of Iraq, into Darfur’ or ‘Boots on the Ground’. When children and teenagers are mobilized in support for war, they should be seen as child soldiers, whether in Africa or America. The difference is that the mobilization around Darfur is not presented by Save Darfur as a political mobilization for war, but as a moral crusade – which is what makes it attractive to millions of people in the US.

Save Darfur has many parallels with the War on Terror. One is presenting Save Darfur as a moral crusade rather than a political option. Second is obscuring the political and social causes of violence, instead claiming that violence is its own explanation, so that the only way to end violence is with more violence. Presumably, the difference is that ‘their’ violence is bad violence but ‘ours’ is good violence.

Have you been surprised that your arguments evoke strong reactions among activists, but also among Sudanese/Darfurians living in the US as witnessed during the debate with John Prendergast in April 2009?

I am not surprised that a critique of the politics of Save Darfur would evoke a strong reaction from activists associated with the organization, be they Americans or Sudanese.

What is your response to the charge raised by some people you would be an apologist of the regime in Khartoum?

I would like to put my response to this question in a context. That context is the ways in which Save Darfur has marketed the conflict in Darfur to the American public, in the process distorting both its nature and its consequences. There have been at least five distortions.

The first concerns the numbers who have died. As early as 2006, a panel of experts appointed by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) in conjunction with the Academy of Sciences concluded that Save Darfur claims of 400,000 dead were highly misleading and that 120,000 as the estimate of excess deaths during the high point of the conflict in 2003-04 – made by CRED, the WHO-associated research unit in Belgium – was more reliable.

The second distortion arises from the assumption in Save Darfur publicity that all those who died were necessarily killed, when WHO data showed that 70 to 80 % had died of the consequences of drought and desertification, and 20-30 % of direct violence. According to CRED: ‘We estimate the number of violence-related deaths to be +/- 35,000.’

This is not to deny that further research is necessary to pinpoint how many of those who died of dysentery and diarrhea may have survived in the absence of violence.

Third, Save Darfur publicity has obscured the history of the violence, and therefore both the fact that it is issue-driven and the responsibility for it. This conflict began as a civil war inside Darfur in 1987-89 against the backdrop of a colonial-era carving up of Darfur into a series of tribal homelands which discriminated against pastoralists and in favor of settled peoples. As a result, camel nomads of the north, who have no settled villages and move throughout the year, have no homeland. Then came the four decade long drought which extended the boundaries of the Sahara another hundred kilometers to the south, pushing the camel nomads towards central Darfur.

The result was a classic ecological conflict (1987-89) between peasant and nomad tribes over the best land: Whoever would control the most productive land would survive the drought. The final contributing cause was the spillover of the Cold War from across the border in Chad, a consequence of its incorporation into the intensified Cold War during the Ronald Reagan presidency. The day after Ronald Reagan became president of the U.S., he declared Libya a terrorist state. Soon after, Chad turned into a Cold War battleground, with one side in the civil war supported by the U.S., France and Israel and the other by Libya and the Soviet Union. If one was in power in Ndjamena, the other crossed the border into Darfur.

It is in Darfur that the opposition gathered, organized, armed and trained and from which it mounted operations. In the process, Darfur became militarized. In the mid-80s, when there was no water in Darfur, the province was awash with guns. It is the ubiquitous AK-47 and the mortars and the bazookas, by and large a Cold War contribution, that made for the lethal violence of the civil war. The important point is that the big powers were implicated in Darfur long before the Government of Sudan was. In fact, the present Government in Sudan came into power only at the end of the civil war in 1989.

Fourth, Save Darfur spread the idea that the violence of the war was perpetrated by ‘light-skinned Arabs’ against ‘dark-skinned Africans’ when the issue that drove the civil war of 1987-89 was not race but land, and the issue that came to overlay it with the insurgency of 2003 was that of power.

Finally, Save Darfur has continued to claim that the violence continues (‘the genocide continues’, says Save Darfur) when all evidence point to a dramatic decline in the level of violence in Darfur with the entry of the African Union in 2004. Only last month, the UN Secretary General’s envoy to Sudan briefed the Security Council that the number of deaths from violence in Darfur had averaged less than 150 from January 2008 to April 2009, and that Darfur was no longer an emergency but ‘a low intensity conflict’.

If we strip away the distortions of this marketing campaign – the numbers who died, the multiple causes of death suggesting that most of those who died were not killed, the fact that the conflict began as a civil war in which the great powers were implicated, that this was a conflict over land and not a race war between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Africans’ and, finally, that the level of violence has diminished markedly since late 2004 – then we come to the kernel of the question of responsibility. I have written that the Government of Sudan carried out its own little War on Terror in Darfur in 2003-04; its result was the massacre of civilians in Darfur in 2003-04. No one can deny that the political power in Sudan, which is the al-Bashir Government, must be held politically responsible for this, much as the De Klerk government in South Africa was politically responsible for the crimes of apartheid in the period before the post-apartheid transition.

The issue I raised in the book was not about the political responsibility of the al-Bashir government, which is a settled issue so far as I am concerned. Rather, I raised a larger and more important issue: how to end the conflict in Darfur. Like apartheid-era South Africa, Darfur is an ongoing conflict. As in the South African case, we are faced with a choice: either try those politically responsible for the killings or win them over to an agenda of political reform. Let us remember that, instead of being tried and imprisoned, the leaders of apartheid sit in a post-apartheid parliament. The same is the case with the leadership of Renamo in Mozambique. And that same choice was made in ending the civil war in South Sudan. Why not in Darfur?

Do you think a US/Western mass movement concerned with the wars and conflicts in Sudan is desirable at all? If yes – how would such a movement ideally look like from your point of view?

Do you think a US/Western mass movement concerned with the wars and conflicts in Sudan is desirable at all? If yes – how would such a movement ideally look like from your point of view?

I think such a movement is highly desirable. It should, first of all, be a peace movement and not a mobilization for war like Save Darfur. Second, instead of a moral crusade that obscures the politics of war and conflict, such a movement should highlight the political context of the conflict and thereby promote a discussion of political choices. The result would be to focus public attention on the issues that drive the violence, rather than a claim that violence is its own explanation. Third, such a movement should educate the public that a durable solution will not be possible without internal support, and without a process capable of healing internal rifts, rather than making the public believe that African problems can only have external solutions. Such an education would have the advantage of teaching the public the difference between solidarity and intervention.

What do you think your book Saviors and Survivors has to teach us about the Sudan that transcends other important contributions like those by Flint/de Waal and Prunier?

I like to think that I have learnt from those who wrote earlier by standing on their shoulders. Specifically, my book brings to light the following dimensions not found in the writings of Flint/de Waal and Prunier: I provide a critique of the dominant historiography of Sudan which underlies the assumption that ‘Arabs’ are a distinct race that immigrated into Sudan as ‘settlers’ over centuries. Instead, I bring together the writings of several authors, Western and Sudanese, to show that the ‘Arab’ tribes of Sudan did not migrate from anywhere but are actually indigenous groups that became Arabs at different points in time: the royalty in the 16th and 17th century, the merchants in the 18th century, and the popular classes much later. In other words, Sudanese Arabs are African Arabs, which is why it makes no sense to talk of a conflict between Arabs and Africans in Sudan or in Darfur.

Second, I show that whereas Arab tribes of contemporary Sudan have been associated with power and privilege in the riverain areas, particularly in the north, the opposite has been the case with the Arab tribes of Darfur who are the poorest and the least educated of all tribes in Darfuri society and at the same time the least represented of all tribes in the state apparatus in Darfur. In other words, if Darfur has been marginal to Sudan, the Arab tribes of Darfur have been doubly marginalized, both inside Darfur and in Sudan.

Third, I show that the issue at the heart of the conflict – land – cannot be understood unless placed in the context of the colonial experience. It is colonialism that created tribal homelands in Darfur, distinguished between ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ tribes in each homeland, and acknowledged ‘customary’ right to both land and administrative positions for those belonging to ‘native’ tribes. In other words, colonialism turned ‘tribe’ from a principle of identity into a basis for sustained and institutionalized discrimination.

Fourth, I show that the conflict in Darfur began as a civil war (1987-89) and not as an insurgency against the central government in Khartoum. This is the big difference between Darfur and South Sudan. I also show that both sides in the civil war saw themselves as victims. At the reconciliation conference in 1989, one side accused the other of perpetrating genocide (in fact using the word ‘Holocaust’) whereas the other side claimed to be the victim of ‘ethnic cleansing’ by those claiming to be natives. By characterizing the conflict in Darfur as ‘genocide’, Save Darfur was taking on the point of view of one side to the conflict. The result has been a partial narrative that has highlighted the demand for an ‘Arab belt’ during the civil war but has obscured the corresponding demand for an ‘African belt’ during that same war. The larger result has been a demonization of Arab tribes of Darfur, blocking them out of political processes, such as Abuja.

Finally, I show that there are two possible ways ahead for Darfur and Sudan. The first is the way of Nuremburg, which is marked by two assumptions: a fight to the finish so the victor would provide the framework of justice – Victors Justice – and a separate future for yesterday’s victims in a separate homeland, a version of Israel. The second is the way of post-apartheid transition, one suited to situations of ongoing conflicts which, if we waited for a victor to emerge, would lead to even greater bloodshed. To settle these conflicts, however, we need to recognize both yesterday’s perpetrators alongside yesterday’s victims as survivors with political rights in the future; thus I call it Survivors Justice. For the whites and blacks in South Africa, as for Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda, and for the tribes of Darfur – whether nomadic and pastoral, or Arab and non-Arab – there is no choice but to live together. There will be no Israel for any of them.

At some of the last pages of your book, you deal with the widely popular call among refugees and inhabitants of Darfur for a military intervention by the West. Doesn’t pose this reality a profound contradiction for an analyst who is much more in favour of an internal or African solution for these conflicts?

Yes it does. I prefer to be realistic and to recognize the existence of profound political problems in most African countries – not only Darfur and Sudan, but also others like Chad, Congo, Zimbabwe, Kenya and so on – where the government of the day rules with impunity and the opposition looks for a quick fix in terms of an external solution.

You caution against taking the call for Western intervention as a kind of ‘false consciousness’. On the other side, you allege those in Darfur calling for foreign intervention are naive and victims of a ‘consumer mentality’. Thus, isn’t that the same as presuming a ‘false consciousness’?

So long as intervention is driven by big power interests and ignores the nature and balance of forces internally, it will only exacerbate the problem instead of ameliorating it.***

My review of the following books will be published on this blog soon:

Mahmood Mamdani 2009. Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror. Pantheon.

Julie Flint, Alex de Waal 2008. Darfur: A Short History of a Long War. Revised Second Edition. Zed Books.

Gérard Prunier 2008. Darfur. A 21st Century Genocide. Third Edition. Cornell University Press.

Photo: ‘Save Darfur’ Rally in Washington, 30 April 2006.

From http://www.ssrc.org/blogs/darfur/2009/05/14/saving-darfur-gender-and-victimhood/

Ruben your interview with the Professor Mamdani was quite enlightening, however I wish to comment as follows-

I expected Prof. Mamdani to at least recognize and appreciate the humanitarian efforts of the Save Dafur organisation. The group could have chosen to ignore the pathetic and deplorable situation in Darfur and focus their attention elsewhere as other groups / governments within the African continent and elsewhere have done. Inspite of the African Unions’ intervention there are still appalling humanitarian disaster in the Darfur enclave. Not much resources are coming from the continent to address the issue. Therefore organisations like Save Darfur should be encouraged rather than condemned.

The statistics reeled by the Professor (while quoting GAO and CRED) is interesting. He noted that as against 400,000 claimed by Save Darfur to have died from the conflct, that only about 120,000 people actually lost their lives whether directly or indirectly from the conflict. I have these questions for prof Mamdani – Even if only 10 persons died from the violence is it not bad enough? Assuming prof Mmadani lost any of his children, wife, father or mother in the conflict, would the loss only be a set of statistics to him? It is not about number but about human beings with hopes, aspirations and perhaps dependants that unfortunately lost their lives. He termed the Darfur conflict “ecological conflict” – my question- should efforts be channelled in proffering solutions to the problem of nature or should scarce resource be expended in aggravating the consequences of ecological degradation, as has being the case with the Sudanese government’s involvement in the conflict?

I’m happy Prof Mamdani acknowledged the deplorable role of the Sudanese leader in the killing of Darfurians though I dont understand why the term “little terrorism”. This kind of language leaves one with an impression that prof Mamdani may not be very sincere in condemning the actions of the Sudanes leadership in the Darfur crisis, but for the overwhelming evidence which clearly implicated Al Basir. This brings me to another issue – why must those who commit war crimes be set free? Should we sacrifice justice for Darfurians (living or dead) in the alter of reconcialiation and reforms? Would it not be better if war criminals are punished as deterrent for those who may choose that evil path in Sudan or elsewhere in future?

Regarding the Prof’s assertions about the limitations of external solutions in addressing African problem, I wish to note that when internal actors and other elements are not providing honest, unbiased and commited solutions, why can’t we welcome external interventions. Having said that I also note that in some instances the motives behind some external interventions may be questionable. Just as Prof. Mamdani noted, colonialism may contribute in destablising the African continent even after the post colonial era. The British legacy and the post colonial political rivary/struggle for dominance between the Southern and the Nothern political hegemony in Nigeria is a case in point.

[…] SDAP mentioned before, that’s what Prendergast said in response to Mahmood Mamdani’s claim that the save Darfur movement’s high school aged activists are “child soldiers.” I always […]

Mahmood Mamdani and the Anti-Imperialism of Yesteryear

You can read in this review why I think one can learn more about the Sudan by studying Flint/de Waal or Prunier rather than Mahmood Mamdani’s new book ‘Saviors and Survivors’, which is deeply committed to an antiquated anti-Imperialism of the Cold War era (German only).

https://rubeneberlein.wordpress.com/2009/08/04/mamdani-saviors-survivors-sudan-waal-prunier-review/